Exploring the X Window System and Related Concepts

TL;DR

The X Window System (commonly known as X11 or simply X) is a windowing system for bitmap displays, primarily used on Unix-like operating systems. Developed as part of Project Athena at MIT in 1984, it became the foundation for graphical interfaces on Unix-based systems. The protocol, currently at version 11 (hence “X11”), has been around since 1987 and is still widely used, managed by the X.Org Foundation.

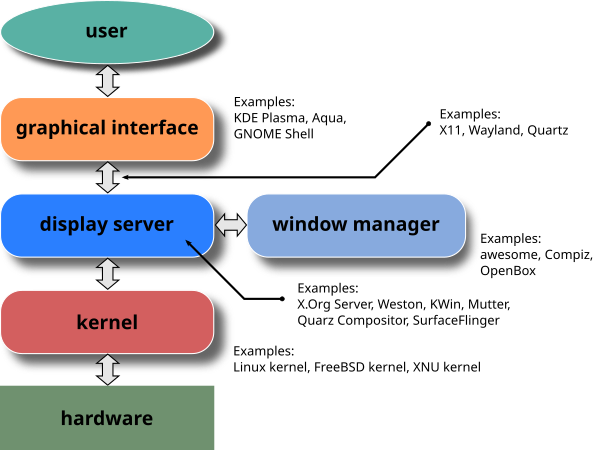

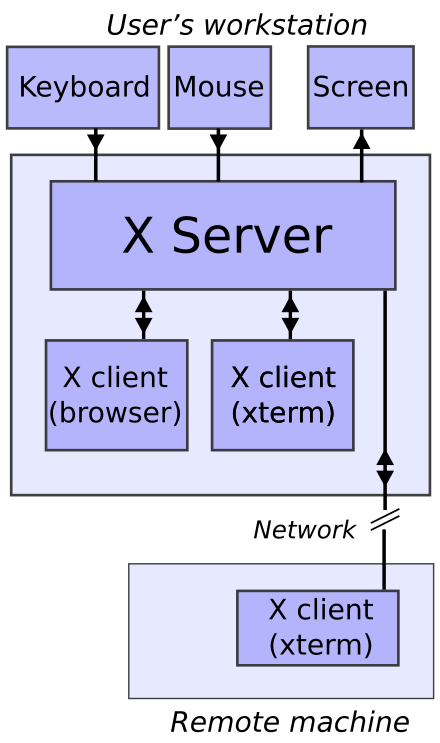

At its core, X provides the infrastructure to create and manage windows on bitmap displays. It separates the underlying hardware from the graphical user interface (GUI), allowing applications to interact with the display hardware without needing direct control over it. X allows windows to be drawn on the screen, handles user inputs like keyboard and mouse events, and enables the concept of a client-server model, where the display (X server) manages graphical requests from applications (X clients).

In-depth View of X11

1. Technical Details & Definitions

Windowing System

A windowing system is a software suite that manages the various windows on a computer display, a vital component of any graphical user interface (GUI). It provides the structure for displaying different parts of the screen and allows multiple applications to run simultaneously within separate windows. A windowing system implements the WIMP (Windows, Icons, Menus, Pointer) paradigm and is crucial for managing the interaction between the user and the operating system.

In a typical setup, each application is assigned a rectangular surface to present its interface, known as a window. These windows can be resized, moved, and may overlap each other, creating the user-friendly environment we’re accustomed to. Window decorations, such as title bars and buttons, are often drawn around these windows for better management and control. This interaction is further simplified through widget toolkits, which provide graphical components like buttons, sliders, and other interactive elements.

Bitmap in Relation to X11

In the context of the X Window System, a bitmap refers to a grid of pixels that forms an image. A bitmap display is an image where each pixel corresponds to a specific value representing color. The X Window System handles these bitmaps to display images and graphical user interfaces (GUIs) on the screen.

Bitmaps are central to how graphical systems represent and manipulate images. For instance, when an application creates a window, the content inside the window (icons, images, text, etc.) is represented as bitmaps that the X server draws on the display. As a raster image format, the bitmap consists of individual pixels organized in rows, where each pixel holds a value defining its color.

2. X11 Components

In this section, I’ll be discussing xdm only, as it was the subject of search that the professor deemed intersting to look at.

xdm: X Display Manager

xdm stands for X Display Manager, which is a graphical login manager for X11. It provides the interface for logging into a system in a graphical environment. Once the login credentials are entered, xdm starts an X session and manages the display connections. Essentially, it facilitates the transition from the console to the graphical user interface and ensures that the X server is correctly initiated.

xdm is part of a broader category of display managers, which are responsible for starting the display server and handling user authentication, session management, and even different environments (such as GNOME, KDE, or i3). While xdm was historically one of the first display managers for X11, it has been largely replaced by more modern equivalents like gdm (GNOME Display Manager) and lightdm.

What Does "?xdm?" Mean When Running Commands Like w or who?

When running terminal commands like w or who, which list logged-in users and their session details, you might occasionally see ?xdm?. This occurs when the terminal is trying to identify the session source or type but is unable to fully determine it. Instead of listing a proper terminal type (like tty or pts), it shows ?xdm?, indicating that the session was started by xdm or a similar display manager.

Typically, this signifies that the session is graphical and was initiated via xdm rather than through a standard terminal login. Graphical sessions don’t always have a physical terminal (TTY) associated with them, so the system marks it with ?xdm? to show that it was initialized by the X Display Manager, as opposed to the traditional text-based terminals.

For example, the output of the w command might look like this:

USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT

logan :0 :0 10:48 ?xdm? 4:16 0.73s init --user

logan pts/3 :0 10:59 3.00s 0.19s 0.01s w

In this output, the graphical session (:0) shows ?xdm? in the IDLE column, indicating that the system cannot determine or track idle time for that session. In contrast, the terminal session (pts/3) shows a specific idle time of 3.00s, demonstrating that the system can monitor idle states for terminal sessions.

Note: Why we see two entries of the same user when running w command

The reason we see two entries for the same user in the w command output is that we have multiple sessions or processes running under the same user. Specifically, the output shows that two processes are associated with the user logan:

logan :0 :0: This entry shows the userloganlogged into the graphical interface session (:0is the display server’s session for X or Wayland). The commandinit --useris related to the systemd process managing the user’s session in the background.logan pts/3 :0: This entry shows the userloganhas a terminal session open (pts/3is a pseudo-terminal, indicating a terminal emulator inside the graphical session). The commandwwas executed in this terminal.

Each session is listed separately because they are different types of sessions (graphical vs terminal).

Conclusion

The X Window System and its components form the backbone of graphical user interfaces in many Unix-like systems. From window management to bitmaps and display managers like xdm, each part plays a vital role in delivering a smooth, interactive user experience. Understanding these components—along with nuances like seeing ?xdm? in terminal commands—gives deeper insight into the workings of graphical interfaces on Linux and other systems.